Introduction

This document (notebook) provides examples of monadic pipelines for computational workflows in Raku. It expands on the blog post “Monad laws in Raku”, [AA2], (notebook), by including practical, real-life examples.

Context

As mentioned in [AA2], here is a list of the applications of monadic programming we consider:

- Graceful failure handling

- Rapid specification of computational workflows

- Algebraic structure of written code

Remark: Those applications are discussed in [AAv5] (and its future Raku version.)

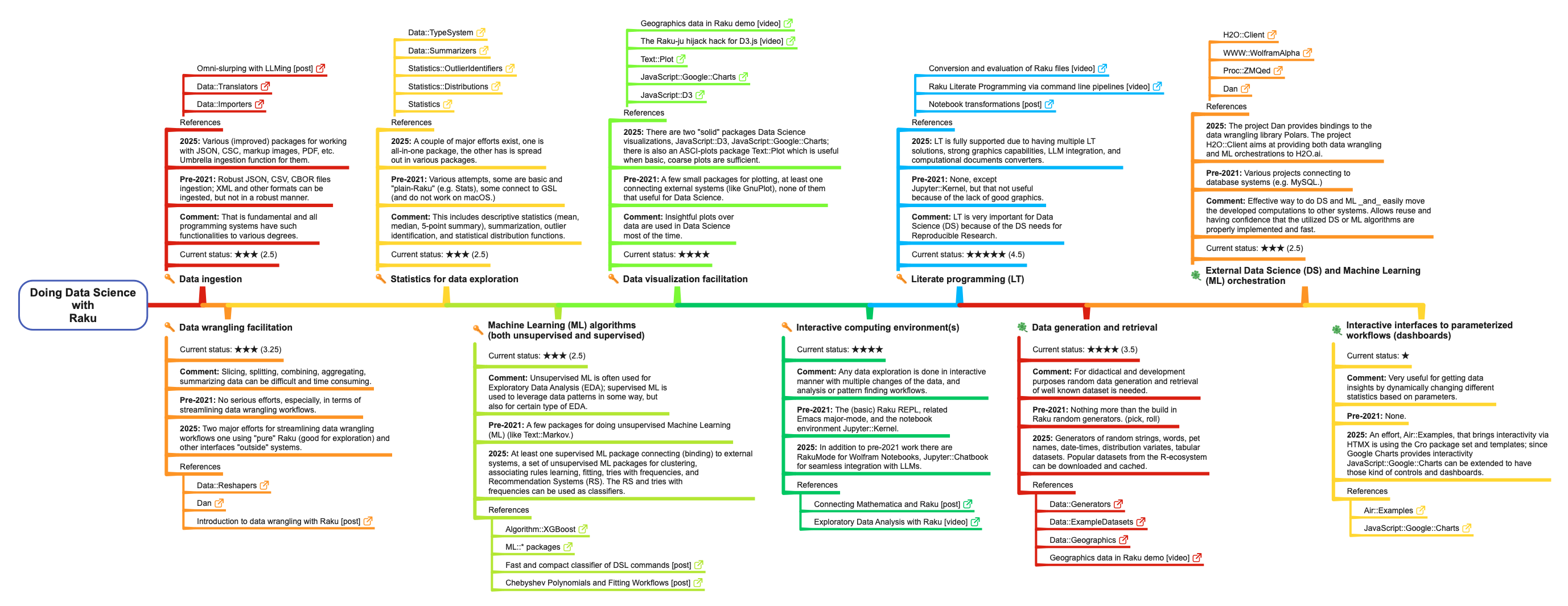

As a tools maker for Data Science (DS) and Machine Learning (ML), [AA3],

I am very interested in Point 1; but as a “simple data scientist” I am mostly interested in Point 2.

That said, a large part of my Raku programming has been dedicated to rapid and reliable code generation for DS and ML by leveraging the algebraic structure of corresponding software monads, i.e. Point 3. (See [AAv2, AAv3, AAv4].) For me, first and foremost, monadic programming pipelines are just convenient interfaces to computational workflows. Often I make software packages that allow “easy”, linear workflows that can have very involved computational steps and multiple tuning options.

Dictionary

- Monadic programming

A method for organizing computations as a series of steps, where each step generates a value along with additional information about the computation, such as possible failures, non-determinism, or side effects. See [Wk1]. - Monadic pipeline

Chaining of operations with a certain syntax. Monad laws apply loosely (or strongly) to that chaining. - Uniform Function Call Syntax (UFCS)

A feature that allows both free functions and member functions to be called using the sameobject.function()method call syntax. - Method-like call

Same as UFCS. A Raku example:[3, 4, 5].&f1.$f2.

Setup

Here are loaded packages used in this document (notebook):

use Data::Reshapers;

use Data::TypeSystem;

use Data::Translators;

use DSL::Translators;

use DSL::Examples;

use ML::SparseMatrixRecommender;

use ML::TriesWithFrequencies;

use Hilite::Simple;

Prefix trees

Here is a list of steps:

- Make a prefix tree (trie) with frequencies by splitting words into characters over

@words2 - Merge the trie with another trie made over

@words3 - Convert the node frequencies into probabilities

- Shrink the trie (i.e. find the “prefixes”)

- Show the tree-form of the trie

Let us make a small trie of pet names (used by Raku or Perl fans):

my @words1 = random-pet-name(*)».lc.grep(/ ^ perl /);

my @words2 = random-pet-name(*)».lc.grep(/ ^ [ra [k|c] | camel ] /);

Here we make a trie (prefix tree) for those pet names using the feed operator and the functions of “ML::TriesWithFrequencies”, [AAp5]:

@words1 ==>

trie-create-by-split==>

trie-merge(@words2.&trie-create-by-split) ==>

trie-node-probabilities==>

trie-shrink==>

trie-say

TRIEROOT => 1

├─camel => 0.10526315789473684

│ ├─ia => 0.5

│ └─o => 0.5

├─perl => 0.2631578947368421

│ ├─a => 0.2

│ ├─e => 0.2

│ └─ita => 0.2

└─ra => 0.631578947368421

├─c => 0.75

│ ├─er => 0.2222222222222222

│ ├─he => 0.5555555555555556

│ │ ├─al => 0.2

│ │ └─l => 0.8

│ │ └─ => 0.5

│ │ ├─(ray ray) => 0.5

│ │ └─ray => 0.5

│ ├─ie => 0.1111111111111111

│ └─ket => 0.1111111111111111

└─k => 0.25

├─i => 0.3333333333333333

└─sha => 0.6666666666666666

Using andthen and the Trie class methods (but skipping node-probabilities calculation in order to see the counts):

@words1

andthen .&trie-create-by-split

andthen .merge( @words2.&trie-create-by-split )

# andthen .node-probabilities

andthen .shrink

andthen .form

TRIEROOT => 19

├─camel => 2

│ ├─ia => 1

│ └─o => 1

├─perl => 5

│ ├─a => 1

│ ├─e => 1

│ └─ita => 1

└─ra => 12

├─c => 9

│ ├─er => 2

│ ├─he => 5

│ │ ├─al => 1

│ │ └─l => 4

│ │ └─ => 2

│ │ ├─(ray ray) => 1

│ │ └─ray => 1

│ ├─ie => 1

│ └─ket => 1

└─k => 3

├─i => 1

└─sha => 2

Data wrangling

One appealing way to show that monadic pipelines result in clean and readable code, is to demonstrate their use in Raku through data wrangling operations. (See the “data packages” loaded above.) Here we get the Titanic dataset, show its structure, and show a sample of its rows:

#% html

my @dsTitanic = get-titanic-dataset();

my @field-names = <id passengerClass passengerSex passengerAge passengerSurvival>;

say deduce-type(@dsTitanic);

@dsTitanic.pick(6)

==> to-html(:@field-names)

Vector(Assoc(Atom((Str)), Atom((Str)), 5), 1309)

| id | passengerClass | passengerSex | passengerAge | passengerSurvival |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 960 | 3rd | male | 30 | died |

| 183 | 1st | female | 30 | survived |

| 1043 | 3rd | female | -1 | survived |

| 165 | 1st | male | 40 | survived |

| 891 | 3rd | male | 20 | died |

| 806 | 3rd | male | -1 | survived |

Here is an andthen data wrangling monadic pipeline, the lines of which have the following interpretations:

- Initial pipeline value (the dataset)

- Rename columns

- Filter rows (with age greater or equal to 10)

- Group by the values of the columns “sex” and “survival”

- Show the structure of the pipeline value

- Give the sizes of each group as a result

@dsTitanic

andthen rename-columns($_, {passengerAge => 'age', passengerSex => 'sex', passengerSurvival => 'survival'})

andthen $_.grep(*<age> ≥ 10).List

andthen group-by($_, <sex survival>)

andthen {say "Dataset type: ", deduce-type($_); $_}($_)

andthen $_».elems

Dataset type: Struct([female.died, female.survived, male.died, male.survived], [Array, Array, Array, Array])

{female.died => 88, female.survived => 272, male.died => 512, male.survived => 118}

Remark: The andthen pipeline corresponds to the R pipeline in the next section.

Similar result can be obtained via cross-tabulation and using a pipeline with the feed (==>) operator:

@dsTitanic

==> { .grep(*<passengerAge> ≥ 10) }()

==> { cross-tabulate($_, 'passengerSex', 'passengerSurvival') }()

==> to-pretty-table()

+--------+----------+------+

| | survived | died |

+--------+----------+------+

| female | 272 | 88 |

| male | 118 | 512 |

+--------+----------+------+

Tries with frequencies can be also used for finding this kind of (deep) contingency tensors (not just some shallow tables):

@dsTitanic

andthen $_.map(*<passengerSurvival passengerSex passengerClass>)

andthen .&trie-create

andthen .form

TRIEROOT => 1309

├─died => 809

│ ├─female => 127

│ │ ├─1st => 5

│ │ ├─2nd => 12

│ │ └─3rd => 110

│ └─male => 682

│ ├─1st => 118

│ ├─2nd => 146

│ └─3rd => 418

└─survived => 500

├─female => 339

│ ├─1st => 139

│ ├─2nd => 94

│ └─3rd => 106

└─male => 161

├─1st => 61

├─2nd => 25

└─3rd => 75

Remark: This application of Tries with frequencies can be leveraged in making mosaic plots. (See this MosaicPlot implementation in Wolfram Language, [AAp6].)

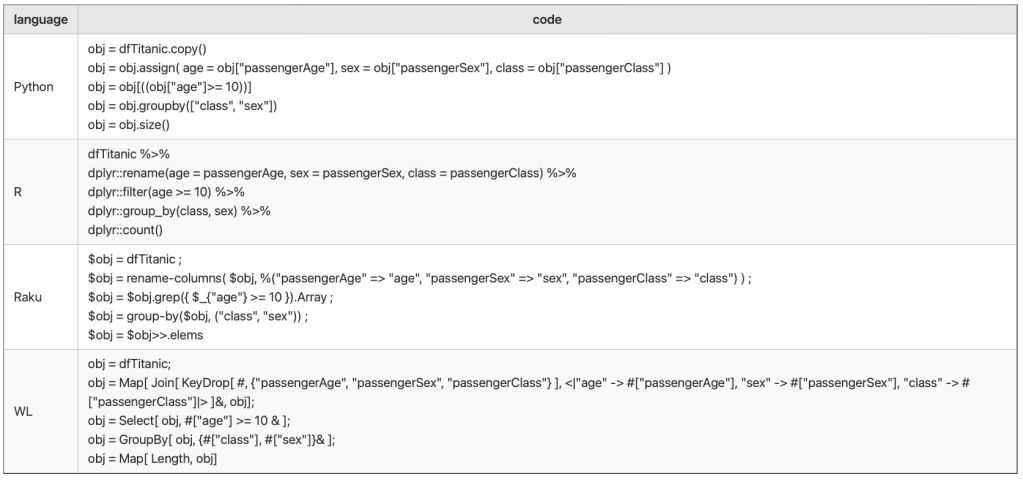

Data wrangling code with multiple languages and packages

Let us demonstrate the rapid specification of workflows application by generating data wrangling code from natural language commands. Here is a natural language workflow spec (each row corresponds to a pipeline segment):

my $commands = q:to/END/;

use dataset dfTitanic;

rename columns passengerAge as age, passengerSex as sex, passengerClass as class;

filter by age ≥ 10;

group by 'class' and 'sex';

counts;

END

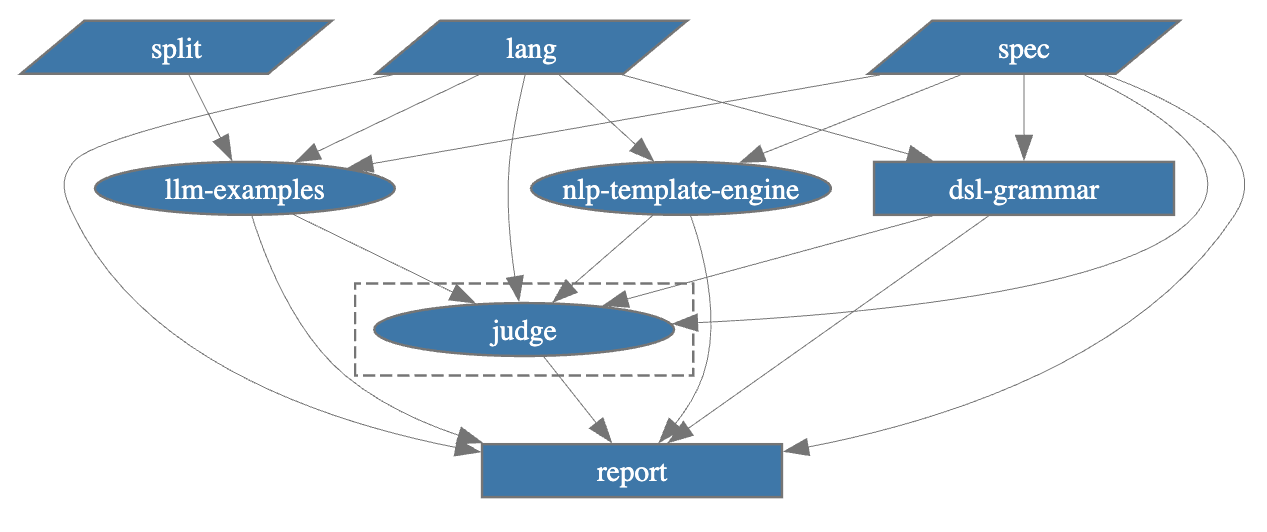

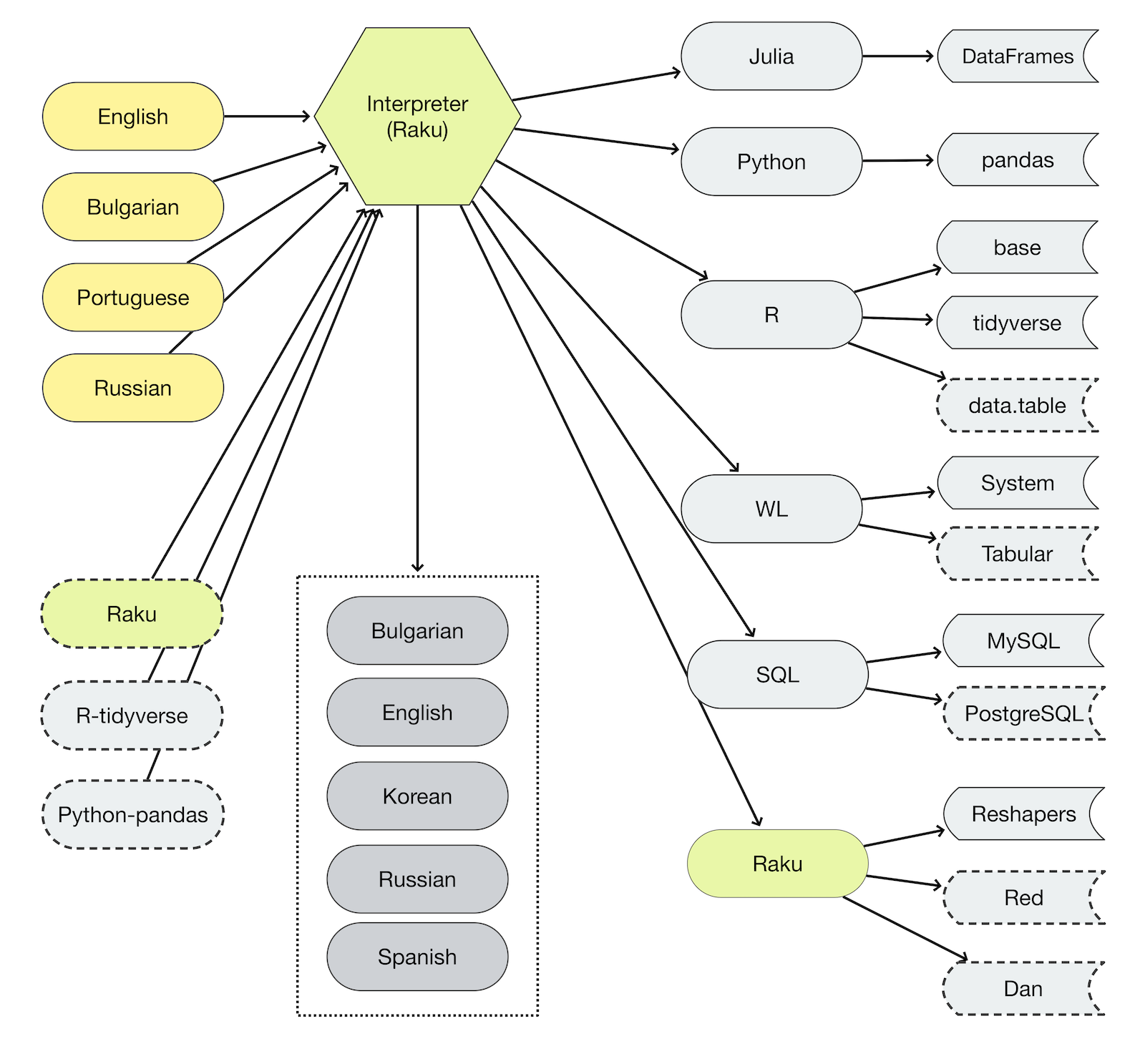

Grammar based interpreters

Here is a table with the generated codes for different programming languages according to the spec above (using “DSL::English::DataQueryWorkflows”, [AAp3]):

#% html

my @tbl = <Python R Raku WL>.map({ %( language => $_, code => ToDSLCode($commands, format=>'code', target => $_) ) });

to-html(@tbl, field-names => <language code>, align => 'left').subst("\n", '<br>', :g)

Executing the Raku pipeline (by replacing dfTitanic with @dsTitanic first):

my $obj = @dsTitanic;

$obj = rename-columns( $obj, %("passengerAge" => "age", "passengerSex" => "sex", "passengerClass" => "class") ) ;

$obj = $obj.grep({ $_{"age"} >= 10 }).Array ;

$obj = group-by($obj, ("class", "sex")) ;

$obj = $obj>>.elems

{1st.female => 132, 1st.male => 149, 2nd.female => 96, 2nd.male => 149, 3rd.female => 132, 3rd.male => 332}

That is not monadic, of course — see the monadic version above.

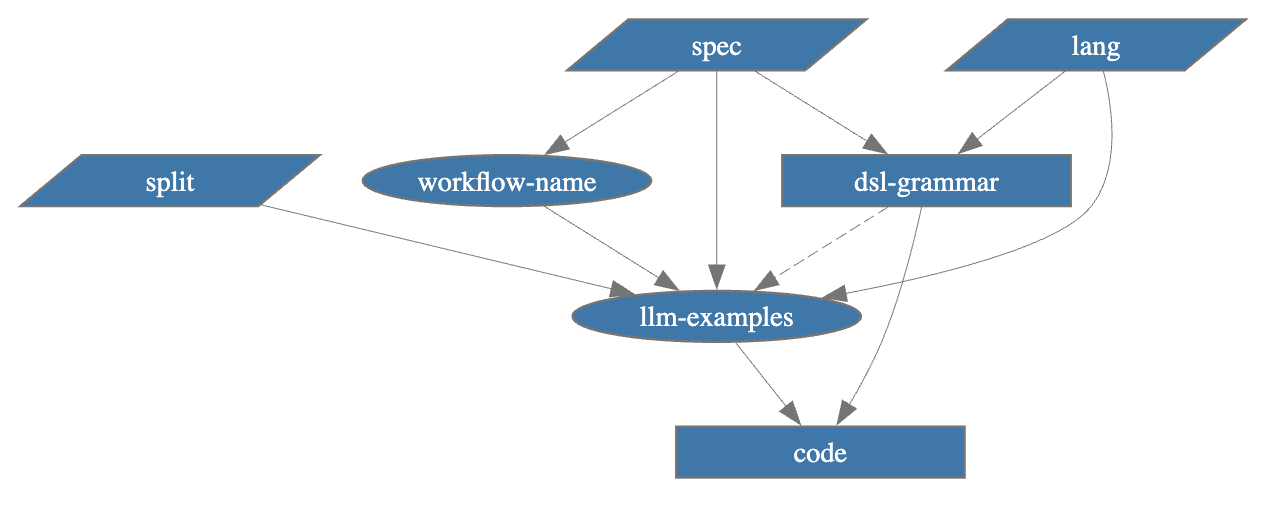

LLM generated (via DSL examples)

Here we define an LLM-examples function for translation of natural language commands into code using DSL examples (provided by “DSL::Examples”, [AAp6]):

my sub llm-pipeline-segment($lang, $workflow-name = 'DataReshaping') { llm-example-function(dsl-examples(){$lang}{$workflow-name}) };

Here is the LLM translated code:

my $code = llm-pipeline-segment('Raku', 'DataReshaping')($commands)

use Data::Reshapers; use Data::Summarizers; use Data::TypeSystem

my $obj = @dfTitanic;

$obj = rename-columns($obj, %(passengerAge => 'age', passengerSex => 'sex', passengerClass => 'class'));

$obj = $obj.grep({ $_{'age'} >= 10 }).Array;

$obj = group-by($obj, ('class', 'sex'));

$obj = $obj>>.elems;

Here the translated code is turned into monadic code by string manipulation:

my $code-mon =$code.subst(/ $<lhs>=('$' \w+) \h+ '=' \h+ (\S*)? $<lhs> (<-[;]>*) ';'/, {"==> \{{$0}\$_{$1} \}()"} ):g;

$code-mon .= subst(/ $<printer>=[note|say] \h* $<lhs>=('$' \w+) ['>>'|»] '.elems' /, {"==> \{$<printer> \$_>>.elems\}()"}):g;

use Data::Reshapers; use Data::Summarizers; use Data::TypeSystem

my $obj = @dfTitanic;

==> {rename-columns($_, %(passengerAge => 'age', passengerSex => 'sex', passengerClass => 'class')) }()

==> {$_.grep({ $_{'age'} >= 10 }).Array }()

==> {group-by($_, ('class', 'sex')) }()

==> {$_>>.elems }()

Remark: It is believed that the string manipulation shown above provides insight into how and why monadic pipelines make imperative code simpler.

Recommendation pipeline

Here is a computational specification for creating a recommender and obtaining a profile recommendation:

my $spec = q:to/END/;

create from @dsTitanic;

apply LSI functions IDF, None, Cosine;

recommend by profile for passengerSex:male, and passengerClass:1st;

join across with @dsTitanic on "id";

echo the pipeline value;

END

Here is the Raku code for that spec given as an HTML code snipped with code-highlights:

#%html

ToDSLCode($spec, default-targets-spec => 'Raku', format => 'code')

andthen .subst('.', "\n.", :g)

andthen hilite($_)

my $obj = ML::SparseMatrixRecommender

.new

.create-from-wide-form(@dsTitanic)

.apply-term-weight-functions(global-weight-func => "IDF", local-weight-func => "None", normalizer-func => "Cosine")

.recommend-by-profile(["passengerSex:male", "passengerClass:1st"])

.join-across(@dsTitanic, on => "id" )

.echo-value()

Here we execute a slightly modified version of the pipeline (based on “ML::SparseMatrixRecommender”, [AAp7]):

my $obj = ML::SparseMatrixRecommender.new

.create-from-wide-form(@dsTitanic)

.apply-term-weight-functions("IDF", "None", "Cosine")

.recommend-by-profile(["passengerSex:male", "passengerClass:1st"])

.join-across(@dsTitanic, on => "id" )

.echo-value(as => {to-pretty-table($_, )} )

+----------------+-----+--------------+-------------------+----------+--------------+

| passengerClass | id | passengerAge | passengerSurvival | score | passengerSex |

+----------------+-----+--------------+-------------------+----------+--------------+

| 1st | 10 | 70 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 101 | 50 | survived | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 102 | 40 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 107 | -1 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 11 | 50 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 110 | 40 | survived | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 111 | 30 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 115 | 20 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 116 | 60 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 119 | -1 | died | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 120 | 50 | survived | 1.000000 | male |

| 1st | 121 | 40 | survived | 1.000000 | male |

+----------------+-----+--------------+-------------------+----------+--------------+

Functional parsers (multi-operation pipelines)

In can be said that the package “FunctionalParsers”, [AAp4], implements multi-operator monadic pipelines for the creation of parsers and interpreters. “FunctionalParsers” achieves that using special infix implementations.

use FunctionalParsers :ALL;

my &p1 = {1} ⨀ symbol('one');

my &p2 = {2} ⨀ symbol('two');

my &p3 = {3} ⨀ symbol('three');

my &p4 = {4} ⨀ symbol('four');

my &pH = {10**2} ⨀ symbol('hundred');

my &pT = {10**3} ⨀ symbol('thousand');

my &pM = {10**6} ⨀ symbol('million');

sink my &pNoun = symbol('things') ⨁ symbol('objects');

Here is a parser — all three monad operations (⨁, ⨂, ⨀) are used:

# Parse sentences that have (1) a digit part, (2) a multiplier part, and (3) a noun

my &p = (&p1 ⨁ &p2 ⨁ &p3 ⨁ &p4) ⨂ (&pT ⨁ &pH ⨁ &pM) ⨂ &pNoun;

# Interpreter:

# (1) flatten the parsed elements

# (2) multiply the first two elements and make a sentence with the third element

sink &p = { "{$_[0] * $_[1]} $_[2]"} ⨀ {.flat} ⨀ &p

Here the parser is applied to different sentences:

['three million things', 'one hundred objects', 'five thousand things']

andthen .map({ &p($_.words.List).head.tail })

andthen (.say for |$_)

3000000 things

100 objects

Nil

The last sentence is not parsed because the parser &p knows only the digits from 1 to 4.

References

Articles, blog posts

[Wk1] Wikipedia entry: Monad (functional programming), URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_(functional_programming) .

[Wk2] Wikipedia entry: Monad transformer, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_transformer .

[H1] Haskell.org article: Monad laws, URL: https://wiki.haskell.org/Monad_laws.

[SH2] Sheng Liang, Paul Hudak, Mark Jones, “Monad transformers and modular interpreters”, (1995), Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages. New York, NY: ACM. pp. 333–343. doi:10.1145/199448.199528.

[PW1] Philip Wadler, “The essence of functional programming”, (1992), 19’th Annual Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages, Albuquerque, New Mexico, January 1992.

[RW1] Hadley Wickham et al., dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, (2014), tidyverse at GitHub, URL: https://github.com/tidyverse/dplyr .

(See also, http://dplyr.tidyverse.org .)

[AA1] Anton Antonov, “Monad code generation and extension”, (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at WordPress.

[AA2] Anton Antonov, “Monad laws in Raku”, (2025), RakuForPrediction at WordPress.

[AA3] Anton Antonov, “Day 2 – Doing Data Science with Raku”, (2025), Raku Advent Calendar at WordPress.

Packages, paclets

[AAp1] Anton Antonov, MonadMakers, Wolfram Language paclet, (2023), Wolfram Language Paclet Repository.

[AAp2] Anton Antonov, StatStateMonadCodeGeneratoreNon, R package, (2019-2024),

GitHub/@antononcube.

[AAp3] Anton Antonov, DSL::English::DataQueryWorkflows, Raku package, (2020-2024),

GitHub/@antononcube.

[AAp5] Anton Antonov, ML::TriesWithFrequencies, Raku package, (2021-2024),

GitHub/@antononcube.

[AAp6] Anton Antonov, DSL::Examples, Raku package, (2024-2025),

GitHub/@antononcube.

[AAp7] Anton Antonov, ML::SparseMatrixRecommender, Raku package, (2025),

GitHub/@antononcube.

[AAp8] Anton Antonov, MosaicPlot, Wolfram Language paclet, (2023), Wolfram Language Paclet Repository.

Videos

[AAv1] Anton Antonov, Monadic Programming: With Application to Data Analysis, Machine Learning and Language Processing, (2017), Wolfram Technology Conference 2017 presentation. YouTube/WolframResearch.

[AAv2] Anton Antonov, Raku for Prediction, (2021), The Raku Conference 2021.

[AAv3] Anton Antonov, Simplified Machine Learning Workflows Overview, (2022), Wolfram Technology Conference 2022 presentation. YouTube/WolframResearch.

[AAv4] Anton Antonov, Simplified Machine Learning Workflows Overview (Raku-centric), (2022), Wolfram Technology Conference 2022 presentation. YouTube/@AAA4prediction.

[AAv5] Anton Antonov, Applications of Monadic Programming, Part 1, Questions & Answers, (2025), YouTube/@AAA4prediction.